Of the five American admirals lost during World War II – the only war

in which we lost any – two were killed in action in the same desperate surface engagement. It was also

the only time in our history that two flag officers – each posthumously awarded

the Medal of Honor – fell on the same day, in the same battle. Part of the

costly 6-month struggle for

Guadalcanal, the

furious and seemingly hopeless night battle of Friday, November 12-13, 1942 and

the 48 hours of combat to follow – the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal - marked a

turning point in the campaign. Defeat was no longer a real possibility. Few now recall how desperate those days were. The

opening phase of that terrible night battle witnessed both heroism and mistakes of deployment and maneuver were made

on both sides, but no one deserves more credit for the ultimate outcome - strategic victory - than

does Daniel Judson Callaghan.

Born in

San Francisco on July 26, 1890,

Dan Callaghan came from a religious Catholic family that had immigrated to the

United States fifty years earlier from

County Cork, Ireland. Educated in parochial

schools in the Bay Area, and inspired by Admiral James Raby, an uncle who had

attended

Annapolis, Dan won a senatorial

appointment as first alternate to the

Naval Academy,

where he quickly earned a reputation for his steady and serious demeanor. He graduated

#38 (of 193) in the Class of 1911, which also included his friend, Norman

“Scotty” Scott of Indiana who ranked near the bottom of their class.

Transferred to the cruiser

New

Orleans as executive officer in 1916, he spent

World War I on convoy escort duty and was promoted to Lieutenant in March 1918,

followed by promotion to Lt. Commander in 1921. By1938, he was serving as Naval Aide to

President Roosevelt (above photo with the King and Queen of Great Britain). Realizing that war was inevitable, however, he pushed hard

for a transfer and in May of 1941, was named skipper of the 10,000-ton heavy

cruiser

USS San Francisco (CA-38). Known in the Navy as

“Uncle Dan”, he was in

Pearl Harbor

for an overhaul on December 7, 1941 and was untouched.

Promoted to Rear Admiral, Dan Callaghan was next appointed Chief of

Staff to Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, newly named Commander, South Pacific

Area. When Ghormley was relieved, Admiral William “Bull” Halsey took over and Callaghan

took command of a cruiser Task Force with his flag on the

San Francisco. On the night of November 12-13, 1942, a powerful Japanese force of battleships, cruisers and destroyers came down the 'slot' to pound Henderson Field and knock it out once and

for all.

Callaghan deployed his ships according to Battle Disposition “Baker

One”, a single column of three groups - four destroyers in the Van Unit,

followed by the five cruisers in the Base Unit, with four destroyers in the

Rear Unit. This arrangement facilitated ease of navigation and maneuver in the

narrow channels near

Guadalcanal. The light

cruiser USS

Helena spotted the enemy early in the battle, but with the

chance for surprise lost, the battle quickly became what one sailor described

as, “a barroom brawl after the lights have been shot out.”

Callaghan realized that survival depended on maintaining the fire of

his largest ships even at the risk of friendly fire. He issued his final

command to the gunnery officer, “We Want the Big Ones; Get the Big Ones First!”

It was both an order and a prayer. The

Japanese battleships continued to pound

San Francisco, which suffered 45 large caliber and countless smaller hits during the

battle. There was undoubtedly friendly fire in the night action. Two minutes later, Callaghan was dead along with

Pearl

Harbor Medal of Honor hero Captain Cassin Young. The badly damaged

USS

San Francisco fought the enemy to a standstill, helped cripple the Japanese Battleship

Hiei

sank a destroyer and was still on station when the enemy withdrew. Many crewmen were decorated.

Adm. Norman Scott

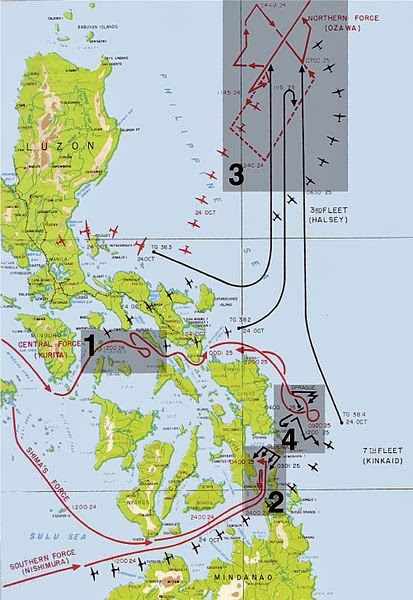

It was one of the most sunning reversals in naval history, evocative of the Battle of Samar 25 October 1944, also characterized by a great disparity in forces. But the cost of stopping the enemy was very heavy. In addition to the

loss of several destroyers – along with their captains - the

USS Atlanta was

lost along with Dan's classmate and friend Admiral Norman "Scotty" Scott, commanding the other surface cruiser Task Force. During the battle the cruisers

USS Portland and

Juneau were badly damaged,

and the latter was sunk the next day by enemy submarine

I-26 along with Captain Lyman K. Swensen and nearly all hands, including all five Sullivan brothers.