“In no

engagement of its entire history has the United

States Navy shown more gallantry, guts and gumption than

in those two morning hours between 0730 and 0930 off Samar .”

Samuel Eliot Morison, Official Naval Historian

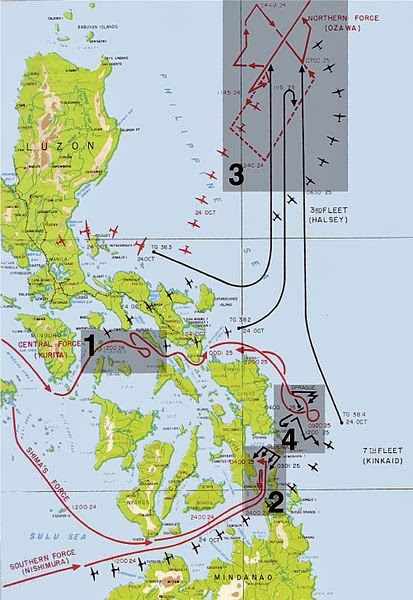

By the dawn of 25 October

1944 it looked like the battle – the biggest and most complex in

naval history – would end in a tremendous American victory. Submarines, surface

forces and naval aircraft each in turn pummeled the Japanese fleet and caused

great damage. Three enemy battleships, two cruisers, and two destroyers had

been sunk and the same number of ships had been badly damaged. Thousands of

Japanese sailors had lost their lives. Our own losses – one light carrier sunk,

a cruiser damaged, and a few dozen aircraft lost, as well as nearly a thousand

men killed, wounded, or missing - had been relatively light compared to the

damage inflicted. Admiral William “Bull” Halsey’s Task Force 38 was at that

moment hunting down the last of Admiral Ozawa’s carriers.

With the Japanese fleet now retiring in every direction, the 175,000 soldiers of the US Sixth Army in theLeyte beachhead and the fleet of transports lying

unprotected off shore were safe. The Liberation of the Philippines – the realization of MacArthur’s

promise to return and redeem the sacrifice of the men of Bataan and Corregidor – would proceed to its inevitable victorious

conclusion. The elaborate Japanese SHO-1

plan had ended in total failure.

At daybreak of October 25, theJOHNSTON JOHNSTON

With the Japanese fleet now retiring in every direction, the 175,000 soldiers of the US Sixth Army in the

At daybreak of October 25, the

Before that, Evans had served as Executive Officer of the ALDEN,

a “four piper” WWI-era destroyer that had survived the terrible early WWII battles

which annihilated Admiral Thomas Hart’s U.S. Asiatic Fleet. After the final

Allied defeat at the Battle of the Java Sea in

late February 1942, the ALDEN had escaped to Australia

Just 20 minutes

after sunrise, a patrol pilot over “Taffy Three” radioed a stunning

message, his excited voice crackling over the ships’ radios. “Enemy surface

force of 4 battleships, 7 cruisers, and 11 destroyers at 20 miles north your

task group and closing 27 knots.” Vice

Admiral Takeo Kurita’s First Striking Force – the most powerful enemy surface

fleet ever sortied - had suddenly appeared undetected and was bearing down on

the helpless beachhead. Nothing stood between the enemy and the complete

annihilation of the invasion forces except the tiny escort carriers of “Taffy Three”,

their few outdated Wildcats and bombers, and their outgunned destroyers. Large caliber shells where already striking the vulnerable carriers, esp. GAMBIER BAY.

The JOHNSTON

In describing

the suicidal charge of the destroyers, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz said “The

history of the United States Navy records no more glorious two hours of

resolution, sacrifice, and success.” The JOHNSTON Johnston

No comments:

Post a Comment